by Jason Wilson, Philly.com.

DOES ANY foodstuff carry as much baggage for Americans as escargot or foie gras? When it comes to escargot, it can be hard to move beyond the old pop-cultural image of snail as “snob food.” Plus, for many newbies, there’s a primal, knee-jerk repulsion to the animal itself or to the presentation that, when done badly, can look like boogers. And when it come to foie gras — the third rail of the food world — it’s difficult to steer any discussion of fatty duck or goose liver away from the ethical or political and back toward the culinary.

The fact is, you can’t open a French restaurant and not have both on the menu. Of course, bringing up the French immediately means a certain strain of “Amurican” gets his back up. I began thinking about the cultural significance of snails this week, because Thursday is National Escargot Day, which will be marked by special menus at numerous restaurants in Philadelphia.

I love escargot. I mean, what’s not to love? When done well — meaning plump and meaty rather than shriveled and boogerish — it becomes a deliciously textured delivery vehicle for bubbling butter and garlic and herbs. But I realize that, for some, snails still represent a dividing line that they will not cross. It’s a shame. If this describes you, why not take the opportunity to try escargot this week? Come on, it won’t kill ya.

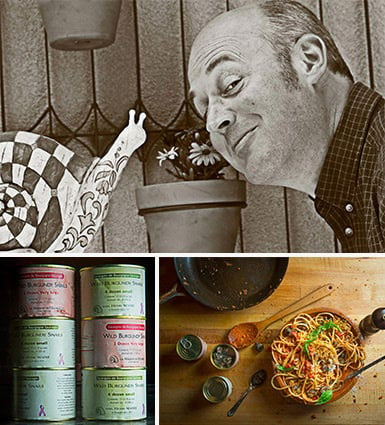

National Escargot Day was the brainchild of Doug “The Snailman” Dussault, whose company Potironne is the prime importer of wild Burgundy snails from Henri Maire, considered by many to be the best snail purveyor in the world. The snails are gathered by hand, then poached in a classic court-bouillon before being packaged and shipped.

Given the image of escargot, it’s surprising how affordable they actually are. A can of two dozen costs around $16 online. “I really like getting snails in front of people,” said the Snailman. “It’s a spectacular protein. It’s organic. It’s nutritious. Snails should be in everyone’s diet.” A serving, Dussault said, has less than 60 calories — this, of course, before the obligatory butter and garlic. “Texture is the biggest challenge,” he said. “But people who eat mushrooms will see there’s something similar about the texture.”

Peter Woolsey, chef-owner of Bistrot La Minette — which is celebrating National Escargot Day with a special menu — calls snails the “seafood of the land,” with a texture similar to mussels or clams but earthier in taste. “It has a seafood quality, but it’s not seafood.” “I have a special affinity for it,” Woolsey said. “My wife is from Burgundy, and when I visit my in-laws, these snails are literally in their garden. But if you see it alive, it’s icky looking.”

For decades escargot was portrayed in popular culture as foodstuff for the wealthy. Through the 1960s and 1970s — “the Fondue Years” as the Snailman calls them — escargot was the ultimate symbol of sophistication. “It was a sign of affluence. It was a sign of being worldly,” he said. Of course, the opposite also happened. Not appreciating escargot was portrayed as a lack of sophistication. Think Julia Roberts in “Pretty Woman.”

This highfalutin’ and aspirational image of escargot persisted well into the 1990s. Consider, for instance, the late rapper Biggie Smalls who, in his classic “Hypnotize,” left us with the immortal line, “I can fill ya wit real millionaires---/Escargot, my car go…”

Lately, the snail business has been great for the Snailman, with March being his best month since he began importing wild snails in 1999. At that time, Dussault had just finished cooking school at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris and had been working at the famed French restaurant Taillevent. “The only thing that came into the kitchen in a can were these wild Burgundy snails,” he said. When he returned home, Dussault started Potironne and became the American importer of snails from that company. He found immediate demand from high-profile French chefs in the U.S.

Daniel Boulud in New York was his first customer.

The Snailman, however, has chosen Philadelphia as the city to personally celebrate National Escargot Day for the past couple of years. “The response I get in Philadelphia for snails is unlike anything else,” said the Snailman. “It has to reflect the caliber of chef, and the caliber of diners in the city.”

While there may be an increase of love for snails, there’s been a growing backlash against the other French bistro staple, foie gras. Animal-rights activists deplore what they call the “force feeding” of ducks and geese and have lobbied to ban the food in many cities and states. On July 1, California will be the first state with a law banning foie gras. More than 100 of California’s highest-profile chefs have petitioned the state assembly to reconsider the ban.

Woolsey does not mince words here: “I think this might be the most fascist thing going on in America right now. Foie gras is more humanely raised than food at McDonald’s. If the government is so concerned about the well-being of geese and ducks, why are they not also banning factory chicken or factory pork?”

Olivier Desaintmartin echoed Woolsey’s sentiments. “Foie gras is an easy target,” he said. “If you ban foie gras, you’ll have to ban a lot of other foods, too.”

In Philadelphia, we are no strangers to activism against foie gras. The heated debate in California reminds Desaintmartin of the mid-2000s, when activists here would show up on busy nights outside his restaurant. “They’d stand six feet from the front door and protest for two hours,” he said. “With a bullhorn.”

While he can’t be sure, Desaintmartin believes anti-foie gras protesters vandalized the front window at Caribou Café. “For five years, I got my window broken every year. And each time, it was when I had a foie gras special written on the window.”

Still, the protesters did little to dampen Philadelphia diners’ enthusiasm. “When the activists were protesting, my diners really pushed the envelope, and ordered more foie gras,” he said. “They weren’t going to be told what to eat.” One side effect of the foie gras debate is that the price has dropped dramatically. Desaintmartin says his foie gras, which he imports from France, has dropped from $35 to $38 per pound a few years ago to around $22 to $24 per pound. He believes that lower prices will have the ironic effect of driving more chefs to use the ingredient. “It’s fun to use, but it’s a tough ingredient to work with. When they say ‘fatty liver,’ they’re not kidding. If you don’t cook foie gras correctly, you could lose 90 to 95 percent of it. It takes a talented hand to make it shine. It took us weeks to come up with our terrine recipe. And the recipe takes 48 hours for us to prepare.”

“But it’s soooo good,” Woolsey said. “Everything that touches foie gras tastes good.”

To buy wild Burgundy snails online, and for recipes: potironne.com.

01-resized-600.jpg)

Jason Wilson has twice won an award for Best Newspaper Food Column from the Association of Food Journalists. He is the author of “Boozehound” and editor of “The Smart Set,” an online arts and culture journal at Drexel University. Follow him at twitter.com/boozecolumnist or go

to jasonwilson.com.

Philadelphia will be playing host to a day completely devoted to a versatile protein that puts a new meaning to the slow food movement.

Philadelphia will be playing host to a day completely devoted to a versatile protein that puts a new meaning to the slow food movement.

The sole importer of helix pomatia, the most succulent of edible snails, Dussault manages a team of foragers who look for the little mollusks in the wilds of France, Italy, Romania and the Czech Republic.

The sole importer of helix pomatia, the most succulent of edible snails, Dussault manages a team of foragers who look for the little mollusks in the wilds of France, Italy, Romania and the Czech Republic.

01-resized-600.jpg)